The Great Wright Road Trip: 9 Architectural Masterpieces

Western Pennsylvania and western New York are blessed with numerous works by famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright – and the settings are just as stunning as the structures. Join Joe Furey on a road trip as he tours nine remarkable sites, including the iconic Fallingwater house.

Photo © Joe Furey

Photo © Joe Furey

Buffalo, New York, had it tough for a while. Dismissed as a post-industrial ruin – its population having fled to the suburbs, its nightlife a couple of bums staring into the Erie Canal – the city had almost forgotten that it used to be somewhere, the eighth largest city in the United States, no less, and one of the most prosperous (in 1901, it had more millionaires per capita than anywhere else in America).

When I first visited, in 1994, “the Queen City” of New York state wasn’t doing so well, and not only because the Bills had just lost their fourth Super Bowl in a row. But even though its heyday had been over for at least 40 years, I could see grounds for hope in its buildings. From the middle of the 19th century, Buffalo was shaped by the best American architects of their generation – Henry Hobson Richardson, Frederick Law Olmsted, Louis Sullivan, and Frank Lloyd Wright – and the city being down on its luck had done wonders for its preservation (empty pockets don’t flatten historic neighborhoods to put up high-rise condos).

Life has been much kinder to Buffalo since, I’m happy to say. The city saw the value of what was staring me in the face all those years ago and invested heavily in it. To see some of the fruits of that investment, I suggest you join me on a little adventure, a road trip dedicated to one of Buffalo’s friendlier ghosts, Frank Lloyd Wright (FLW).

The Great Wright Road Trip (GWRT), a showcase of nine FLW sites, starts in Buffalo, then wends its way through lake-facing western New York to the leafy, rolling Laurel Highlands of southwest Pennsylvania. It would take you seven hours if all you did was roll down your window and drive, so make the trip a journey, a long weekender. You’ll want to savor your surroundings, because Wright’s work is as much about where it is as what it is.

Frank Lloyd Wright sites in Buffalo

Our first stop is the Darwin D Martin House, named for the man who commissioned it, one of Wright’s oldest friends and his chief benefactor (both thankless tasks – the architect, though undoubtedly brilliant, was a libidinous egomaniac and reckless spender, of both his and his clients’ money). Built between 1903 and 1907, the residential estate, comprising the main house and five other structures, including a pergola, is the finest early example of the near instantly iconic “Prairie” style that became FLW’s Hallmark, and an object lesson in attention to detail: Wright designed everything the eye can see there – the furniture, decor, fixtures, gardens, the 394 pieces of stained glass – so it all works in wondrous concert.

After Martin’s death in 1935, the complex fell into what looked like terminal disrepair, but it, and its grounds, have been painstakingly restored – and we can see again why Wright described it as a “well-nigh perfect composition”.

Located in Buffalo’s Parkside neighborhood – the work of Frederick Law Olmsted, who also gave us Central Park – the house is open to the public as a museum, and guided tours are available.

Buffalo has three other Wright buildings, and they share an unusual distinction: none of them were constructed in his lifetime.

Designed in the 1920s for a local oil company, the Filling Station wasn’t built until 2014, and then as a permanent exhibit at the Pierce-Arrow Museum, where it is surrounded by restored antique cars, which the architect, a real autophile, would have loved.

The Fontana Rowing Boathouse, which in the first decade of the 20th century was destined for a site at the University of Wisconsin (Wright’s home state), eventually found a home in 2007 at the West Side Rowing Club alongside the Niagara River. It is open by appointment.

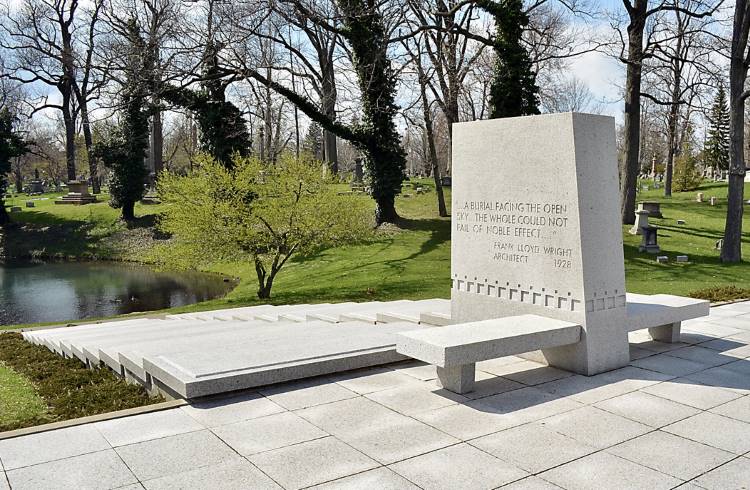

By far the most impressive of the three is the Blue Sky Mausoleum. This modernist masterpiece of Forest Lawn Cemetery in Delaware Park (another Olmsted creation) was commissioned by Darwin D Martin to be the final resting place for his family, but the Wall Street crash of 1929 wiped him out financially, and his wish wasn’t realized.

The design was unusual for its time with a wide terrace set with benches and a modest central stone – rather than a commanding obelisk – on which a quote from Wright is engraved (“a burial facing the open sky … the whole could not fail of noble effect”), with a set of 12 steps, each housing a crypt, on either side, gently descending towards a pond at the foot of the memorial. It is a compellingly transcendent vision, which blurs the boundary not just between structure and setting, but also earth and heaven.

While you’re at the cemetery, do as I did and seek out the grave of Rick James, the funk legend who was buried there in 2004, the year the mausoleum went up. Super Freaks need love too.

Graycliff

From downtown Buffalo, it’s a 25-minute drive south along I-90 to Derby, and Graycliff, the Martin family’s summer home, which looks out over Lake Erie. Built in the late 20s, and so dubbed because it sits on a bluff of grey shale and the Tichenor limestone used in the construction of its three buildings, the handsomely renovated Graycliff truly gives itself to its locale, its broadly cantilevered balconies letting the outside in, the spray of Niagara Falls just visible on the horizon.

For our next stop, and a glimpse into FLW’s working life, stay on the I-90 till you hit Erie, Pennsylvania. His San Francisco office has been lovingly reassembled at the Hagen History Center. And his prized rusty orange 1930 Cord L-29 Cabriolet is also on display.

Polymath Park

Heading south for some 170mi (274km), via I-79 and I-76, will take you to Polymath Park, the “Frank Lloyd Wright oasis”, near Acme, Pennsylvania. A 125-acre resort encircled by private forest, the park features two relocated Wright residences – Duncan House, originally a prefab home in Lisle, Illinois; and Mäntylä House, a mini essay in concrete block, tidewater cypress, and Ludovici tile roof, formerly of Minnesota – and two designed by an apprentice of Wright’s, Peter Berndtson, which are original to the site. All are available for tours, with lunch or dinner, and overnight stays.

Fallingwater

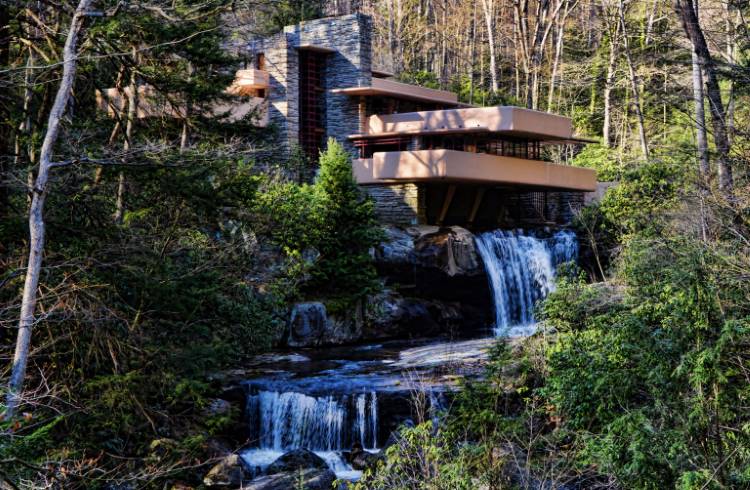

On Route 381, 30mi (48km) south, near Mill Run, is, according to an American Institute of Architects poll, “the best all-time work of American architecture”. Designed in 1935 as a weekend retreat, Fallingwater is Wright’s magnum opus. Legend has it that the concept sprang, like Athena from the head of Zeus, fully formed from Wright’s imagination when his clients called to say they were coming over to view the plans for it and the procrastinating architect had to improvise a full set of drawings in a couple of hours.

Perched above a waterfall on a rocky outcrop, for all its appearance of mass this haut bourgeois house seems to float above God’s own country, while growing out of it, its balconies suggesting deep pools, its interiors somehow cave-like yet spacious and doused with light. It looks, even now, uncompromisingly modern, alien even, but as though it’s been there forever. It has to be seen, at least half a dozen times, to be believed. Tours, except on Wednesdays and holidays, are available.

Kentuck Knob

Our last stop is Kentuck Knob, a mere 6mi (9.6km) down the road from Fallingwater. Completed in 1956, just three years before Wright’s death, this work of art in sandstone, red cypress, copper, and glass is an exceptional illustration of what the architect called his Usonian style – affordable dwellings that were usually single-story, crafted from native materials, naturally cooled and heated, turned away from traffic and towards their environment, and free of architectural conventions.

Blending seamlessly with the landscape, the house manages to feel, at once, cozy and colossal, intimate yet thrown open to the elements by its expanses of glass and the jaw-dropping view of Youghiogheny River Gorge just beyond the back terrace.

What makes Kentuck Knob the perfect spot to end your trip is its sculpture park. More than 30 works – by, among others, Andy Goldsworthy, Claes Oldenburg, Michael Warren, Wendy Taylor, and Sir Anthony Caro – occupy the grounds and woodlands surrounding the house, as well as “found art” pieces such as a French pissoir and a standing slab of the Berlin Wall. Control freak that he was, I’m not sure that FLW would approve, but I do.

Related articles

Simple and flexible travel insurance

You can buy at home or while traveling, and claim online from anywhere in the world. With 150+ adventure activities covered and 24/7 emergency assistance.

Get a quote

No Comments