Tales of Sorrow and Uplift on the US Civil Rights Trail

Launched in 2018 and covering more than 120 sites across 15 states, this trail commemorates the fight for social justice in the US during the 1950s and ‘60s. It’s a must for anyone who wants to understand the troubling history and learn about the inspiring heroes of the movement.

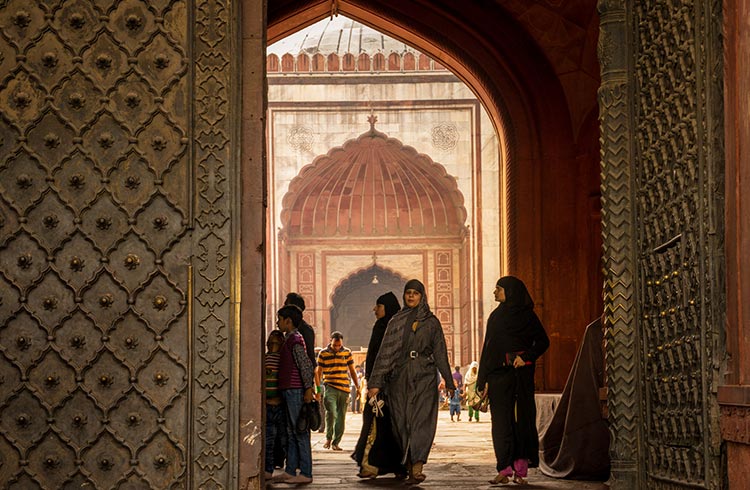

Photo © Joe Furey

Photo © Joe Furey

- The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy

- The seeds of racial justice in Birmingham, Alabama

- Reckoning with the past in Charleston, South Carolina

- Commemorating the Underground Railroad

- Racism in America: not just a Southern problem

It was 1990 when I first encountered racial discrimination of a kind I hoped had long been extinguished in the United States. Having walked off the cramps and nausea of a 10-hour Greyhound ride to Mobile, Alabama, a friend and I made for one of its divey bars.

After 45 minutes of clinking bottles and idle chat, I started to take in the room. The patrons were all white, and the pictures and paraphernalia on the wall included the Confederate flag and campaign posters for George Wallace, Jesse Helms, and Lester Maddox, all famously fierce opponents of the civil rights movement. Then, if a clincher were needed, I heard the bartender refusing admission to a Black sketch artist, “not welcome, not for work, not for play”.

The beer turned to ashes in my mouth. I was mortified to have put money in the pocket of prejudice. Plainly, nothing had changed – not fundamentally – since the Jim Crow period, when laws enforced racial segregation across the South (from the Reconstruction Era, that largely bungled attempt to redress the inequities of slavery and its political, social, and economic legacy after the American Civil War, to the beginning of the civil rights movement in the mid-50s).

I promised myself that I would never be so naive again, and so began my 30 years of study, allyship, and writing on race relations in the United States.

If you want to educate yourself on America’s long, winding, and often bloody road to civil rights, and understand why the nation is still struggling with racial justice, hit the US Civil Rights Trail. Launched in 2018, the trail features more than 120 sites across 15 states, mostly in the South, where activists fought to advance social justice and racial equality in the 1950s and 1960s.

By the time the civil rights movement came into being, “emancipated” Black people across the South had been told where they could walk, how and to whom they could talk, where they could live, work, shop, or be educated for almost a century. And they had been subject to daily torments, from verbal abuse to acts of unconscionable inhumanity.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama

Nowhere is that inhumanity more devastatingly brought home than at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, aka the National Lynching Memorial, which opened in 2018, in Montgomery, Alabama, along with a new Legacy Museum. Together they address the maintenance of white supremacy by racial terrorism in the form of extrajudicial killing and modern mass incarceration.

The vision of Bryan Stevenson, a civil rights lawyer and founder/executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a not-for-profit organization committed to criminal justice reform, the memorial honors each of the more than 4,000 people of color who lost their lives to lynching.

At its center is an open walkway with 800 steel columns hanging from its roof. Engraved on each column is the name of an American county and the people who were lynched there, most listed by name, some as “unknown”. Some of the horrors that befell them are related on plaques fixed to the wall (read them and weep, literally). You meet the columns at eye level first, but as you walk, the floor descends, till by the end, the columns are dangling above you, leaving visitors feeling uncomfortably like the crowds of spectators seen in old photographs (10,000 people gathered to watch Henry Smith, 17, be tortured and burned on a 10-foot scaffold in Paris, Texas in 1893; while 15,000 attended the mutilation and burning of Willy Brown in Omaha, Nebraska in 1919).

Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy

Martin Luther King Jr. connects many of the sites on the Civil Rights Trail. He had been pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery for about a year when, in 1955, he was chosen to lead a boycott of the city’s public bus system after Rosa Parks refused to surrender her seat to a white passenger and was consequently arrested for violating the city’s segregation law.

You can tour King’s childhood home and birthplace at the Martin Luther King Jr. National Historic Site, in Atlanta, Georgia. He was born upstairs because his parents refused to use segregated hospitals, and he and his wife are buried nearby.

The National Civil Rights Museum, in Memphis, Tennessee, incorporates the Lorraine Motel where Sam Cooke, Aretha Franklin, and Otis Redding took rooms, Wilson Pickett composed In the Midnight Hour, and King was gunned down on the balcony on April 4, 1968, leaving a psychic scar on the city that has yet to fully heal. I attended the 50th anniversary commemorations, and spoke to Hampton Sides, who wrote Hellhound on My Trail about the assassination. “I don’t believe King accomplished more in martyrdom than he would have accomplished had he lived,” he said. “We could use him right now. At this time of police brutality, the war on truth. We need his civility, his moderation, his message of non-violence.”

The seeds of racial justice in Birmingham, Alabama

According to King, Birmingham, Alabama, was probably “the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States” and his “Birmingham campaign”, a model of non-violent direct- action protest organized by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1963, drew the country’s attention to the hardships and brutality faced by Black citizens there. In April, King was jailed for two weeks, and on his release the city's Black youth redoubled their insurgency. After a few verses of I Woke Up With My Mind Stayed on Freedom, they burst through the doors of the 16th Street Baptist Church and faced down vicious dogs and fire hoses. Within days, an agreement was forged to desegregate the city. The nation had begun its stagger toward the March on Washington, King's I Have a Dream speech, and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The city now has its own Civil Rights Heritage Trail, which winds through downtown, marking significant locations along the 1963 Civil Rights march routes, including the 16th Street Baptist Church, which was bombed by the Ku Klux Klan in September 1963, killing four young girls.

Reckoning with the past in Charleston, South Carolina

Established in 1851, the 37-acre McLeod Plantation in Charleston, South Carolina, is rare among former plantations in that it makes no attempt to whitewash history. Charleston, though it was built on slave labor (Sullivan’s Island was the point of entry for an estimated 400,000 enslaved Africans brought to British North America), has started to reckon with its ignominious past, and the International African American Museum is slated to open, on the site of a former slave market, in 2022.

Commemorating the Underground Railroad

A “center of education and discourse”, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, in Cincinnati, Ohio, is located on the banks of the Ohio River, which once separated the slave states of the South from the free states in the North. The museum works to keep alive the stories from the Underground Railroad, the secret network of “conductors” (allies) and “stations” (safe places) by which fugitive slaves made their way towards, they hoped, a measure of liberty.

Racism in America: not just a Southern problem

I use the word “measure” advisedly. The story of the civil rights movement may be a Southern one, but racial discrimination was, and remains, a nationwide problem, and it behooves us all, not just during Black History Month, to keep this in mind.

Take “sundown towns”. Products of the Great Migration – between 1916 and 1970 six million Black people left the South in search of work – those towns got their name from the threatening signs they erected that warned people of color they wouldn’t be welcome within their city limits after dark (Anna-Jonesboro, Illinois, had such signs on Highway 127 as recently as 1976).

As I learned from my late friend James Loewen – who wrote the definitive book on the subject and had me visiting sundown towns to record interviews and take photographs for his archive – beginning in about 1890 and continuing until 1968, thousands of towns were established across the US for whites only. Many drove out their Black populations and destroyed their communities, then put up the intimidating signs. Others passed ordinances prohibiting African-Americans and other minority groups from owning or renting property.

This policy may have officially ended decades ago, but discrimination is far from over in the United States. Until there is genuine equality of opportunity, the same racial disparities in economic wellbeing that dogged our past will go on to inform our future.

The Civil Rights Trail is a good reminder of both how far we’ve come and how far we have left to go.

Related articles

Simple and flexible travel insurance

You can buy at home or while traveling, and claim online from anywhere in the world. With 150+ adventure activities covered and 24/7 emergency assistance.

Get a quote

No Comments