Meeting the World’s Authority on Mexican Folk Art

Nomad Maxine tell us about the remarkable woman who single-handedly collected 10,000 works of art.

Photo © Getty Images / Mahaux Charles

Photo © Getty Images / Mahaux Charles

Folk art is never anonymous but rather, always made by an artist, simply one whose name we do not know. - Dr. Ruth Lechuga

While traveling in Mexico City, I heard about a woman named Ruth Lechuga who was the world’s authority on Mexican folk art and had an astonishing collection of 10,000 objects in her apartment.

I knew I had to see her.

Though she was elderly and ill, when I called her, she invited me right over.

I was greeted by her caregiver, served delicious Mexican coffee, and asked to wait a few moments. When Ms. Lechuga arrived, she greeted me in perfect English and told me a bit about herself. Her name had been Ruth Deutsch and she came to Mexico in 1939 with her family at the age of 18, Jewish refugees from Nazi Austria.

“I knew nothing of Mexico nor the Spanish language,” she said, “but when I saw a mural by Jose Clemente Orozco in the city’s Palace of Fine Arts, it sparked a lifelong curiosity about Mexican culture. It was not so much the subject matter as the colors. That night, I dreamt in yellows and reds. Such an intense emotion made me realize that this was a completely different culture that could not be understood through European eyes.”

A lifelong quest

From that moment on, Ruth began a quest to learn about Mexican culture. This was no easy task, as Mexico has dozens of native tribes who speak myriad languages. With her father, she traipsed through the most remote parts of Mexico with her camera slung in front of her. She visited villages where Spanish was never heard and foreigners never

In one village, she became intrigued by a blouse embroidered with brilliant flowers. She bought it, and later she told me, “That blouse had me asking many questions. Who made it? How did they make it and why?” It was followed by

10,000 objects, 10,000 stories

I was feeling somewhat guilty asking so many questions of Ruth. She looked frail as a feather and had to walk with an oxygen tank rolling beside her. Yet, soon I saw my questions seemed to energize her and her voice grew stronger with the passion she felt for the beautiful things in her apartment. And indeed there were many. Her collection spread out on every possible inch of her apartment –

I was enchanted by everything: a row of pretty little dolls made from corn husks, tortoise and horn combs in fanciful shapes (mermaid, mariachi, owl, and bird), metal trays and boxes painted with conquistadors, and masks of angels, devils, animals, and smiling surreal creatures. Pottery bowls and urns of every size and shape to hold mescal and pulque and corn were lined up like a small army. I felt I had entered a dreamlike realm where the humblest object was witty, surprising, and possessed its own unique spirit.

“I have never bought an item without insisting on meeting its maker and learning its purpose,” Ruth declared. “For example, if I bought a mask, I wanted to meet the dancer who had worn it in the sacred ceremony. Once I had to wear the mask and dance with it as a condition of my purchase. The mask was smelly with sweat from the previous dancer, but putting it on and dancing with it made me understand in a visceral way that the mask was not merely a work of art but an instrument for expressing aspects of the human spirit.”

Reflections on life and death

Ruth guided me through her vast collection, even the curious little figurines fashioned from chewing gum. In one room, she introduced me to her teenage grandson, who was busy cataloging her enormous collection of regional embroideries. But after two hours, I worried about tiring her and so began to make my farewell.

“You cannot go yet,” she exclaimed, “you must see my bedroom!”

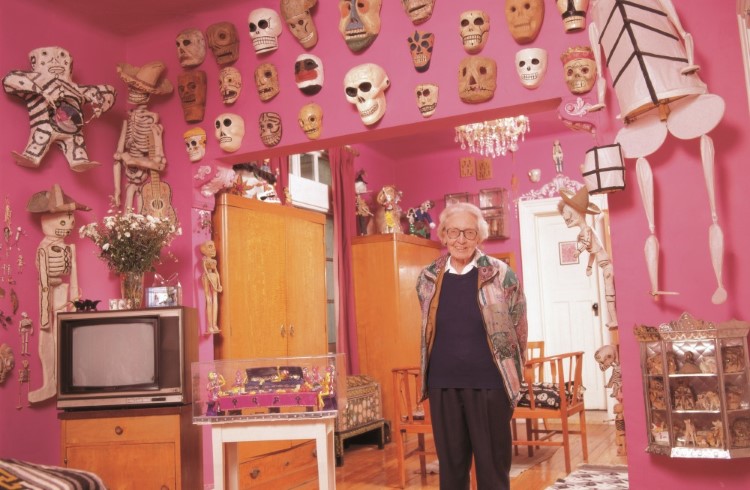

So, I followed Ruth slowly down a long hallway and when we reached her bedroom, I stood in bewilderment. The walls were painted a deep rose pink and at first, I thought they were decorated with white lace. But upon entering, I saw they were covered floor to ceiling with Day of the Dead skeletons, some in tuxedos, some in Marilyn Monroe costumes, and others in a wide variety of dress. At the back of the room, Ruth pointed out a shelf of tiny dioramas showing how death comes as murder. She picked up a small box depicting a tiny man being shot at an ATM window. “Amusing,” she said.

Then, she looked at me with a sly grin. “You know, Death thinks it’s laughing at me but when I lie in bed here and look about my room—I laugh at Death.”

Ruth died less than a year after our meeting. Today her collection is housed in Mexico City’s Franz Mayer Museum. It’s the perfect space, granting Dr. Lechuga the wish she had confided in me:

“I want the collection to be useful, to demonstrate this country’s many roots. This is the real Mexico. As more people are able to see the collection and take part in the adventure of learning about the country, I can say it was put to good use and I didn’t waste my life.”

Trip Notes

Visit the Ruth Lechuga Folk Art Collection at the Franz Mayer Museum, which holds Latin America’s largest collection of decorative arts.

Address: Av. Hidalgo 45, Centro Histórico, Guerrero, 06300, Mexico City

Hours: Tuesday to Friday 10-5, Saturday and Sunday 10-7. Closed Monday.

Related articles

Simple and flexible travel insurance

You can buy at home or while traveling, and claim online from anywhere in the world. With 150+ adventure activities covered and 24/7 emergency assistance.

Get a quote

No Comments