By Sarah Duff

Travel Writer27 Jul 2019 - 5 Minute Read

Meditating isn’t easy for me at the best of times, but throw in 93°F (33°C) heat, high humidity, and holding an exhausting standing pose for 20 minutes, and clearing my mind becomes impossible. Sweat drops roll down my back, my legs are shaking like elastic bands in a breeze, and my arms, held up in a semi-circle as if I’m hugging an imaginary tree, feel like they’re about to fall off. Instead of energy flowing through my body, and my mind emptying, I’m doing 60-second countdowns in my head to help the time pass – and to keep from collapsing in a sweaty heap.

It’s the first morning of a three-week immersion in the martial art of taijiquan at a school in a tiny village in the province of Guangxi, southern China, and I’m not quite sure what I’ve signed up for. I’ve never practiced taiji (also written as “tai chi”) before coming to China, but my partner, Joe, has been a long-time practitioner of the martial art. For years, he’s been convincing me to try what many consider one of the best exercises for longevity and mind-body health. China – the birthplace of taiji – seems like the perfect place for me to start.

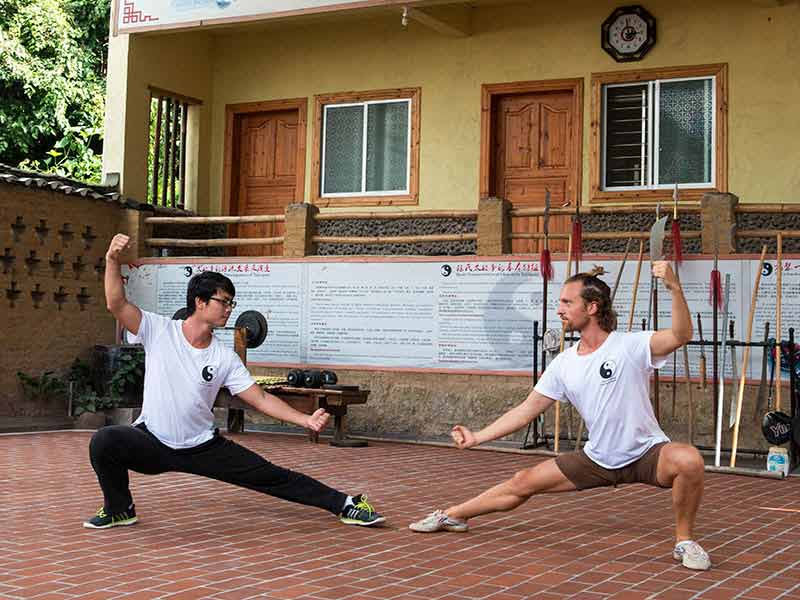

The first thing I learn is that taiji is a lot harder than it looks. After each morning’s gruelling, 20-minute standing qigong meditation, we move on to learning the Chen-style taiji form, a sequence of 74 moving postures developed by Ming Dynasty military officer Chen Wangting in the 17th century. Our teacher and co-founder of the school, the soft-spoken Master Ping, is in his early 30s and has practiced for more than 20 years. When he demonstrates the postures, which flow seamlessly from one to the next, he’s mesmerizing to watch: graceful and fluid, with startlingly quick snatches of power.

Then it’s my turn to try. Simple-looking postures – with names like “White crane spreads its wings” – reveal themselves to be extremely challenging. I thought my mind-body co-ordination and flexibility weren’t too bad, considering all the years of yoga I’ve done, but in this taiji class I’m clumsy and unmalleable. Instead of the feeling I'm supposed to have of water coursing through my body, I feel like my limbs are made of dry, heavy clay.

After three hours of practice, our class of eight breaks for lunch, sitting in a group in the school’s kitchen around a wooden table laden with steaming white rice, tofu in chilli sauce, stir fried egg and tomato, and steamed greens. We have time to rest after lunch, during which I often lie down on my wooden plank bed in my monastically simple room just off the training courtyard. Afternoon training is another three hours, followed by communal dinner, and then an early night’s sleep.

It takes all my concentration to remember the sequence and transition through the movements. My hamster-wheel brain goes from multi-track thoughts to directed attention in an intense kind of mindfulness.

As the days pass in this intensive routine, I make slow progress, getting the hang of each posture before moving onto the next one. It takes all my concentration to remember the sequence and transition through the movements with the precise alignments that Master Ping demonstrates. In these moments, I don’t have the mental space to think about anything else. My hamster-wheel brain goes from multi-track thoughts to directed attention in an intense kind of mindfulness.

I learn as the course progresses that taiji is a kind of meditation in motion. While the martial art is only a few hundred years old, the Taoist philosophical principles it’s based on date back 6,000 years. In Taoist belief, the universe and everything in it derives from the interplay of the opposing forces of yin and yang. Taiji explores this dualism in the body by trying to find a balance between tensing and relaxing muscles, in line with exact body mechanics. This is what’s thought to give taiji its numerous mind and body benefits, which range from improved strength and agility and reduced inflammation to decreased levels of anxiety and stress.

As much as I enjoy the challenges of taiji, I also love my time in this beautiful rural area. In between morning and afternoon sessions, I wander around the tiny village of Jima, comprising just a few houses and small shops, and practice my few words of Chinese with the friendly, elderly locals. On weekends, when we have time off training, I explore the surrounding landscape, renowned in China for its jewel-green rice paddies and hundreds of karst mountains covered in thick foliage. I rent a bicycle to ride through sleepy villages to the town of Yangshuo, where I hike to the top of Green Lotus Mountain for a dramatic panorama of the Li River winding its way through the finger-like pinnacles.

It’s only in my last few days of classes that I experience a kind of breakthrough. Under Master Ping’s gentle guidance in these hours and hours of practice, I’ve developed a muscle memory for the movements and the form, which means I’m now able to concentrate more on trying to cultivate a sense of relaxation in my limbs. My feelings of frustration have passed, and, in their place, there’s quiet focus.

I’ve completed my goal of learning 18 of the 74 postures of the form, and while I still haven’t even begun to feel the yin and yang forces in my body, or the flow of qi (the Chinese concept of energy), I do feel more connected to my body, more grounded, and just that bit calmer in my mind – even when I’m not practicing. I couldn’t ask for a better introduction to the deep and complex world of taiji.

Listen to the World Nomads Podcast - China

Discover similar stories in

transformation

Travel Writer

Sarah is a freelance travel writer, photographer and documentary filmmaker who has been adventuring around the globe on assignments for a decade.

No Comments