By Vincent Roazzi Jr.

Travel Photographer25 Mar 2019 - 6 Minute Read

It’s the most peculiar survival advice I will ever receive, bestowed by a Bhutanese gym trainer during my routine workout in one of the country’s only fitness clubs.

Chencho advises me against bestial encounters of the supernatural kind:

“If a bear attacks you, hit him in the nose – his life force – and he will die instantly.

If a bear walks up to you and smells you breathing, then he will attack you.

If a bear tickles himself under his arm and laughs, then he will attack you…”

I laugh immediately. “Come on!” I say. He replies, “No! It’s true – my grandfather told me.”

“If you see the leaves swirling at your feet, run! That’s the yeti. He will kill you.”

Chencho is not joking, especially not about the yeti, or migoi as it’s known in Bhutan. I’m confused, but I’m not surprised. I’ve lived here almost one year, working for the travel portal MyBhutan, and I struggle every day to figure out this spiritual, folkloric, and often magical culture.

Indeed, I consider it healthy to question everything in life for the purpose of knowing. Lately, however, I’m starting to wonder if skepticism is my easy way out of truly understanding the grayer areas of the world.

I approached Chencho for advice because, in one week, I will hike the mountains at night for the rare opportunity to capture a midnight portrait of Tiger’s Nest Monastery. This past week, my daydreams have been haunted by black panthers, tigers, and Himalayan black bears. I have reason to be concerned – monks recently talked of a bear that visited the temple doors, lured by the smell of butter lamps.

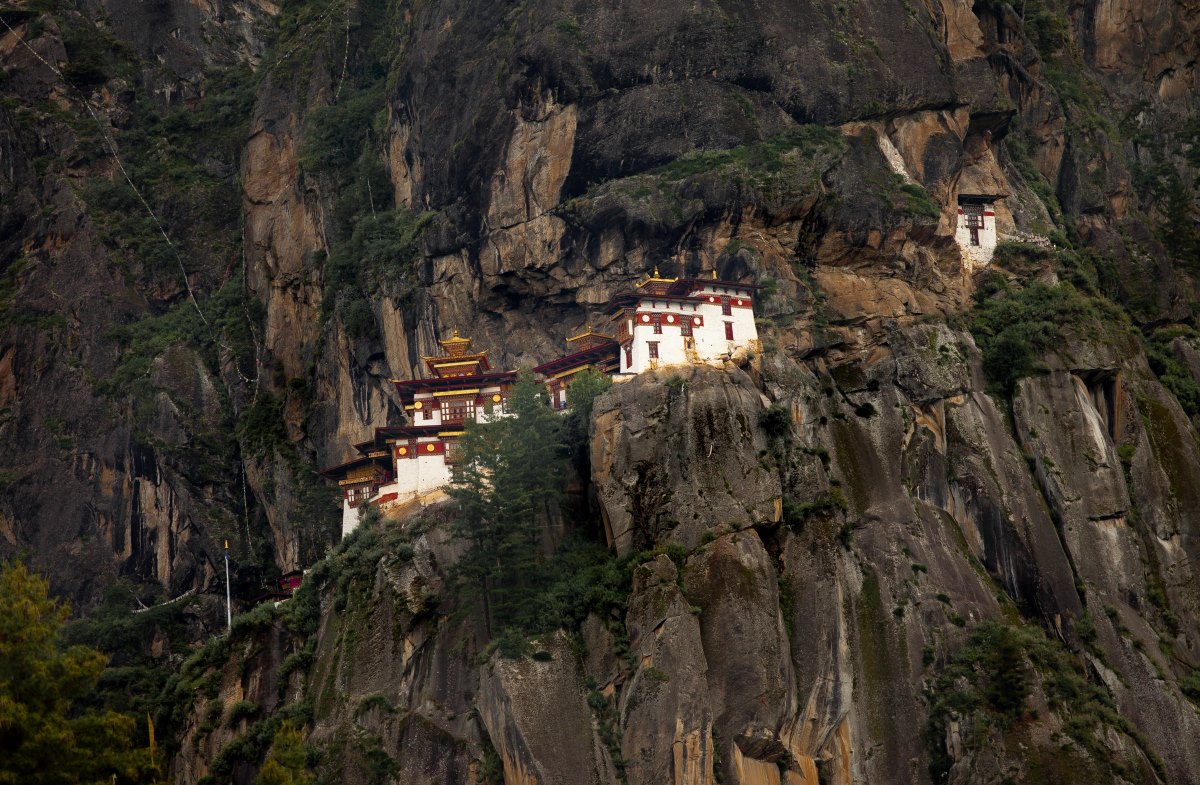

Taktsang, as Tiger’s Nest is called in Dzongkha, is situated at 11,000ft (3,350m) and is considered one of the world’s greatest spiritual journeys. Every Bhutanese tour guide will tell you…

1,300 years ago, Guru Rimpoche, the second Lord Buddha, rode atop a flying tigress and descended upon the site to subdue a local demon. He then meditated in a nearby cave for three years, three months, three weeks, and three days…

…so the story goes.

At 10pm one night, I start at the base of the mountain. I'm accompanied by my friend's nephew, age 18, who's just as timid about the trek as I am. My flashlight beams a short cone of light towards a dirt trail disappearing into the trees. Deep growls ahead preview the sight of stray dogs surrounding us. Wooden tables left behind by villagers vending good-luck charms during the day have been flipped and lie scattered. We carefully step through the scene, me tensely gripping my tripod until the growls quiet behind us.

With this early spike of adrenaline, we continue up the mountain in haste. Bushes shake and branches crack from each direction. “Something is following us,” I say to myself. Predator eyes gleam in front of me, to the side, and from behind. They are everywhere. Indeed, we are being followed.

I hear a treble bell ringing in the distance. We meet a spinning water wheel standing in the middle of the creek, decorated in gold Tibetan inscriptions. Its spin is generated by the water’s downstream energy on an infinite loop. Each spin is said to charge the water with divinity.

I remember the ritual I’ve been taught by my Bhutanese friends:

“Cup your hands to the water, then take a sip. Comb the remaining water over your head. This will wash your karma of bad energy.”

“I’ve never done this right before,” I think to myself, “I’ve only done it out of respect for culture.” I look at the ghostly wheel and consider a divine force, one that could potentially protect me from a beastly nemesis. I recollect other times in my past where I reaffirmed prayer amid dire circumstance, a predictable notion that should never take me by surprise but always does. With my flashlight pointed at the fountain, I cup my hand, take a sip, and focus on the water performing its duty.

After an hour of hiking, a new pack of feral dogs is catching up to us. As they close in, I sense they are harmless and sociable – less successful fighters than their foes at the base. Buddhists here consider dogs equal in the spiritual ranks to humans, which makes dogs well cared for around the country.

I know these curious followers smell the potato chips in my backpack. I welcome them eagerly, as I’m desperate to have members of the animal kingdom on our side. At this point, we're more than half way and turning back would maintain the same risk – I’ll worry about our descent later.

We quickly become a troop, strutting up the mountain with our chests out. The worries and thoughts within my mind start to quiet. The night is brighter now, or so it seems. I look up at the moon and am grateful for the little light it can provide.

With the whipping sound of prayer flags, I know we’ve reached the final cliffside trail. Standing seven feet tall, these white prayer flags have been raised in memory of the dead, and decorate every acre of Bhutan, especially at the highest peaks where the winds are said to carry their prayers.

Another large prayer wheel stands atop the mountain before the final path. The wheel is still, and requires human force to generate its spin. Again, I feel compelled to follow the rituals afforded to me by my Bhutanese friends.

“Turning the wheel of dharma emanates peace over all sentient beings.”

I grab the handle and swing the prayer wheel around three times, an auspicious number.

Our final paces bring us to the edge of the cliff and a clear view of Taktsang. I look closer to see monks making midnight koras, ritual walks around the temple. The monks are praying for everyone and everything, dead and alive, continuously, and with pure intent.

I set up my tripod for a long exposure and think about my previous daydreams about this exact spot: a battle to the death against an anonymous beast, set in an arena of dramatic lighting storms. Even though we still need to descend the mountain, I know the beast and I will never meet, though part of me wishes we would.

I think about my friends back in the capital city on this Friday night, drinking Druk 11,000s at our go-to bar. “Finally, I’ve broken my routine.” I think to myself.

I spend an hour atop the mountain gazing at the temple, until a mist delicately brushes my forehead, hinting of rain – it’s time to go.

Discover similar stories in

fear

Travel Photographer

Vincent Roazzi Jr. is a photographer from New York City with a passion for photographing people and culture around the world.

No Comments