What Are Tourism Pledges And What Are They Trying To Do?

Tourism pledges help us do the right thing when we travel, but do they really change attitudes and behaviors? And how can travelers help make pledges more effective?

Photo © Getty Images / Leo Patrizi

Photo © Getty Images / Leo Patrizi

It’s a tricky line to walk, for any place in the world that wants visitors: how to warmly welcome people to your homeland while also making them aware of how you’d like them to behave, to protect the natural environment and reduce their impact on the people (and other animals) who live there. Introducing rules and codes of conduct might work in some destinations, but there is another, softer way: the tourism pledge.

- What is a tourism pledge, exactly?

- Sign here: destinations with pledges

- How do they work?

- The Palau Pledge anomaly

- Do tourism pledges actually make a difference?

- The road ahead for pledges

- Make your tourism pledge more meaningful

What is a tourism pledge?

It sounds almost too simple, like a relic from a more trusting time: ask travelers to promise to “do the right thing”, whatever that means for a destination. But that’s basically what tourism pledges do, using three key strategies, according to Dr Julia Albrecht, Senior Lecturer in Tourism at the University of Otago, New Zealand: engaging visitors’ emotions (to inspire them to care about the destination) and requiring visitors to take action (rather than passively reading a list of guidelines) and make their promises public.

“The public aspect of the pledge is very important,” says Albrecht, who has studied tourism pledges. “We know from research in areas like psychology and the health sciences that committing to a behavior publicly, for example via social media, can be extremely helpful in causing positive behavior change. So [signing a pledge] is about wanting to keep one’s word, yes, but also wanting to be seen to keep a promise one has made to oneself.”

Sign here: destinations with pledges

The Icelandic Pledge, created by Visit Iceland in the summer of 2017, kicked off the pledge movement, closely followed by the Palau Pledge later that year. Then came New Zealand’s Tiaki Promise in 2018 and the Sustainable Finland Pledge in 2019.

There are also more localized pledges, introduced in popular spots across the US such as: Aspen and Telluride (with its Tell-U-Right Pledge) in Colorado, Bend in central Oregon, and Sedona, Arizona, as well as California’s coastal Big Sur region. The islands of Hawai’i, Kauai and Maui all have their own pledges, as does the Haida Gwaii archipelago in Canada, and Maria Island in Tasmania, Lady Elliott Island in Queensland, and Byron Bay in northern NSW, Australia.

Riding the coattails of these destination pledges are issue-specific pledges. On World Animal Protection’s website, for example, you can pledge to not ride elephants on your next trip, to see dolphins and other animals only in the wild, and to be an animal-friendly traveler. You can promise to avoid air travel for a year, to reduce your carbon emissions, with the Flight Free Pledge. Or take the Travelers Against Plastic pledge to reduce your use of single-use plastics when you travel.

How do pledges work?

Most pledges convey serious messages in a light-hearted way – the Sustainable Finland Pledge uses rhyming couplets like “On my journey, I pledge to be like a Finn, and by this, I mean slowing down from within” – and tend to be written in the first-person “to draw visitors in and deliberately create a personal connection,” says Albrecht.

“Evoking an emotional response in visitors can be very successful in forming conservation intentions in visitors and complements increasing visitors’ knowledge, which is also important because research suggests that people are generally disrespectful out of ignorance, not malice.”

So Kauai’s pledge, for example, includes this line: “I will not stack rocks… as it is offensive to native Hawaiians”. It also ends with “The land is chief, man is his servant” written in Hawaiian and English, like other pledges that use words and values from First Nations cultures. Hawai’i’s Pono Pledge (pono means righteous) asks visitors to malama (care for) the land, the sea, and each other. The Tiaki Promise is named after the Maori word tiaki (to protect, guard, and care for). And the Haida Gwaii pledge uses ancient Haida values such as Yahguudang (respect for all beings), Ad kyaanang (ask permission first) and Tll yahdah (making it right) to communicate how to travel with respect.

The Palau Pledge anomaly

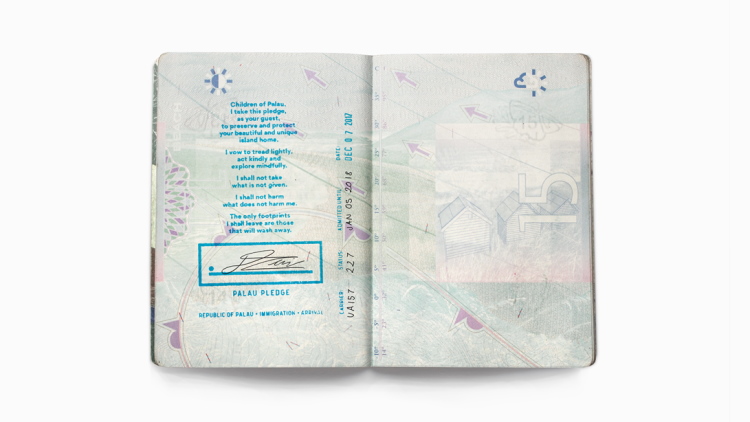

One pledge that has broken away from the pack is the Palau Pledge, which is compulsory, not voluntary like other pledges. The island nation of Palau, famous for its scuba diving and conservation ethos, was the first country in the world to change its immigration laws to require all visitors to sign a pledge stamped into their passports on arrival. There are fines of up to US $1 million for environmental and cultural breaches, and legislation introduced in 2018 ensures all tour operators discuss the pledge with their clients to promote sustainable behavior.

It's also addressed to Palauan children, many of whom helped draft the pledge. “Children of Palau,” it begins, “I take this pledge as your guest, to preserve and protect your beautiful and unique island home.”

Do tourism pledges make a difference?

The short answer: no one really knows. “There has been very little monitoring,” says Albrecht and none of the tourism authorities contacted for this story could provide evidence that their pledges had changed visitor attitudes or behavior – which is understandable. For one thing, pledges tend to be general in nature (“I vow to explore with a sense of responsibility, adventure, and kindness,” says the Maria Island Pledge) without measurable outcomes. Then COVID-related border closures interrupted the flow of tourists (and data) to most destinations for at least two years.

It’s also impossible to isolate the effect of a pledge when it’s part of a broader campaign, as most pledges are. Or to know if a pledge changed visitor attitudes – or vice versa.

World Animal Protection has had more than 1i0,000 to its animal-friendly pledges since the first one (not to ride elephants) was launched in 2016. “We do know that these pledges together speak to a shift in public behavior around wildlife tourism,” says Suzanne Milthorpe, Head of Campaigns at World Animal Protection, “but it's difficult to say if individual pledges on their own help to shift attitudes, or if changing attitudes are resulting in people signing these pledges.”

The road ahead for pledges

But there are hopeful signs. In terms of reach, Palau’s pledge has been wildly successful, if only because signing is compulsory for inbound tourists: more than 1,067,000 have signed since it was launched in late 2017 (although some of those signatories might have been returning visitors).

Post-COVID, some destinations are dusting off their pledges to rebuild tourism more sustainably. A recent Air New Zealand inflight safety video revolved around the 2018 Tiaki Promise. The Aspen Pledge, created in 2018, was relaunched in July 2022 with a financial twist: the Aspen Chamber Resort Association now donates US $18.80 per signature (Aspen was founded in 1880) to local conservation groups and raised more than US $7,000 in its first three months. Palau has developed a world-first app, called Ol’au Palau, to “gamify” responsible travel by awarding travelers points for, say, signing the Palau Pledge or offsetting their carbon footprints, with points used to access places and experiences usually off-limits to visitors.

And new pledges are still being rolled out, such as the Byron Bay Pledge, a community-led initiative launched in Byron Bay in late 2021 as part of “a multi-pronged regenerative tourism pathway” according to co-founder and local eco-tour operator Wendy Bithell.

Make your tourism pledge more meaningful

“We should only sign a pledge if we intend to follow up on the positive behaviors in the pledge,” says Albrecht, “and if that’s the case, there’s no reason not to sign it.” Signing also communicates to tourism authorities that we care about sustainable travel, which can have flow-on effects in terms of infrastructure and policy. A few ways to make your pledge count:

- Sign as close to your arrival in a destination as possible and revisit the pledge during your trip so it stays fresh in your mind, like a responsible travel mantra.

- Make it more public: Some pledges, like the Tiaki Promise, invite you to share your pledge on social media, but even if they don’t, spread the word and share the love.

- Talk to other travelers. “Talk with other travelers and ask if they’ve taken the pledge and what they think about it,” suggests Albrecht. “Starting conversations is always a path towards changing attitudes, particularly when they’re between peers.”

- Talk to the locals. Interacting with people who live in the place you’re visiting – whether it’s a local guide or someone you meet in a cafe – is a great way to understand, in practical terms, why your pledge matters and how you can put it into practice.

- Use pledges to plan. Love travel that benefits people, places, and the planet? Pledges can steer you towards like-minded destinations. Because what could be better than visiting a place that helps us all travel responsibly, sustainably, and regeneratively?

Related articles

Simple and flexible travel insurance

You can buy at home or while traveling, and claim online from anywhere in the world. With 150+ adventure activities covered and 24/7 emergency assistance.

Get a quote

No Comments