Why Traditional Languages Help Preserve Indigenous Cultures

Traditional languages not only help preserve Indigenous cultures, but their presence can also enhance a traveler’s understanding of a destination.

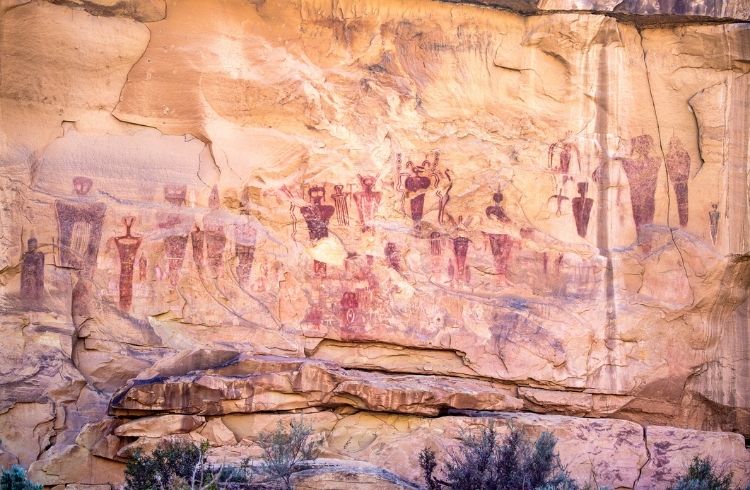

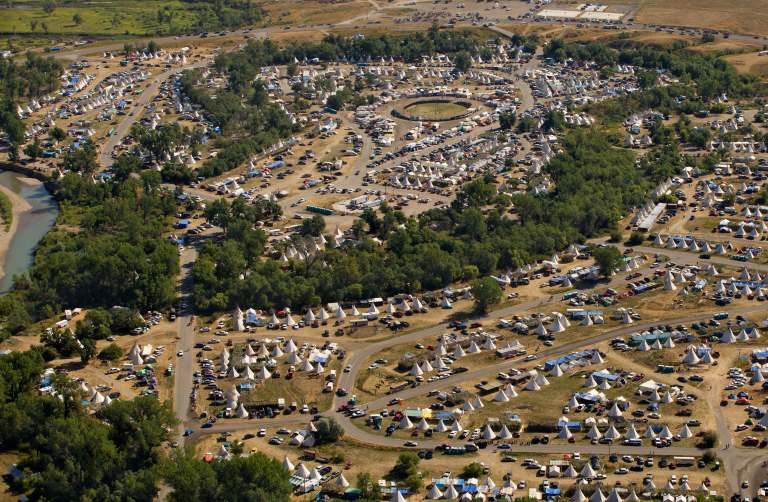

Photo © Getty Images/Penny Tweedie

Photo © Getty Images/Penny Tweedie

- The disappearance of language

- The significance of stripping native names

- Efforts to restore Indigenous names and languages

- Language, context, and storytelling

- The connection of language and identity

- How travelers can help preserve Indigenous languages

The disappearance of language

Despite 7,000 languages spoken across the globe, half of the world’s population speaks only 23 of these languages. The sad truth is that when a language isn’t spoken, it dies, and right now, approximately 90% of the world’s local languages are in danger of disappearing. According to the United Nations, the preservation of Indigenous languages is “the preservation of invaluable wisdom, traditional knowledge, and expressions of art and beauty” that we can’t afford to lose, yet another language dies every two weeks.

Across the Americas, we find examples of how colonization attempted to – and, in some cases, succeeded in – eliminating the languages spoken by local populations. In Trinidad and Tobago, French Creole stopped evolving and is no longer in mainstream use because the language was stigmatized by English colonizers. Across what are now the United States and Canada, Native American tribes were forced into boarding schools where only English could be spoken. The results were devastating.

The significance of stripping native names

Not only did colonizers attempt to eradicate Indigenous languages in their spoken form, but they also tried to remove them from the geographical landscape. Elder Mike Bruised Head of the Blackfoot tribe in Canada explains here how the “demeaning” and colonially imperialistic practice of stripping mountains of their Native names is an “encroachment” on his tribe’s history. The relationship Blackfoot people had with the mountains is so strong that it is even expressed in the surnames of some of the tribes and in the name of spirit animals in the mountains.

Instead of bearing the names that local tribes assigned to the mountains that they lived in and cared for – land that is now part of Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta, Canada – the geography was assigned new names in honor of Western explorers and British elite who had no connection to the land. According to Elder Mike, restoring Indigenous names provides a non-colonial interpretation of the history of Native people in the area.

Efforts to restore Indigenous names and languages

And while Canada has a long history of stripping Native names from the land, the country, and Parks Canada, in particular, is also leading efforts on the continent to restore relations with Indigenous communities. Not only have some traditional names been restored, but Parks Canada has begun returning some power to the people who have historically and currently occupy the land. Torngat Mountains National Parks, which resides within the Inuit homeland, is the only park in Canada that is 100 percent managed by Inuit people, who also serve as park guides.

In Australia, the traditional home of the Butchulla people, K’gari, has resumed being referred to by its Aboriginal name, instead of its “new” and now-former name, Fraser Island. Similarly, in Alaska, Mount McKinley was “renamed” with its original Indigenous name, Denali, which is derived from the Koyukon language. Unfortunately, no efforts have been made to return control of this or any other National Park in the United States to local tribes.

Language, context, and storytelling

Maintaining local languages can help stop the Westernization of peoples and their cultures by giving them the freedom to speak, read, learn, and express on their own terms and in their own words. Mishel McMahon, the Indigenous Student Services Officer at La Trobe University in Victoria, Australia explains quite simply how when language is lost, so is context. “There are teachings in the Indigenous language where there is no English equivalent,” says McMahon. Storytelling has long been a part of Indigenous culture around the world and when a story can’t be told in its original language, crucial context is lost, to the detriment of individual families and to society.

The connection of language and identity

While we often think of the loss of (and efforts to preserve) traditional languages among Indigenous and First Nation people in North America and Aboriginals in Australia, a fascinating example of current language revival efforts comes from Ireland. Until recently, the last feature film made entirely in the Irish language was released 44 years ago but Irish language is now becoming increasingly centered in pop culture, as it’s appearing in more films, music, and books around the country. The Irish author, Manchán Magan describes the connection with one’s language (Irish, in this case), as a sort of portal through which one can understand nature, spirituality, land, and themselves. “You cannot understand Ireland without understanding its relationship with the Irish language,” says Magan.

Meanwhile, just across the water in Scotland, a National Gaelic Language Plan seeks to “encourage and enable more people to use Gaelic more often and in a wider range of situations.” Not only is Gàidhlig (Gaelic) used on Scottish road signs, but there is also a new Scottish Islands Passport mobile app that is geared at travelers. The purpose of the app is to introduce travelers to the history, folk tales, and stories of daily life, all told by local islanders. Each passport stamp includes both English and the local language, be it Gaelic, Shetlandic, or Orcadian.

How travelers can help preserve Indigenous languages

At a bare minimum, seeing Indigenous languages on street signs, informational plaques, and highway markers is a reminder of who lived there long before the streets, plaques, and highways were built. In many corners of the world, it’s possible to spend a week exploring without ever learning that your holiday is occurring on land that was stolen from Native people. Seeing Indigenous languages reinforces the place that Native people have had in history while also recognizing their crucial role in modern society.

Most travelers are not going to begin studying Native languages at home just because they see the language displayed on a road sign. However, you could begin asking more questions about who used to live there, who currently lives there, who is making decisions about the land and its use, and how your tourist dollars could support local Indigenous groups. Many English speakers have grown accustomed to seeing English everywhere they go. We’ve been thoroughly spoiled and have no concept of what it’s like to travel in a land where we can’t understand any of the words around us. Seeing non-English languages present, and, ideally, as the default language, is also an important reminder that English is not the only language on earth and the needs, interests, and comfort of English speakers do not outrank those of local populations.

Seeking out Indigenous-led tourism is one way to support Indigenous communities and can provide some first-hand exposure to Native languages and how they are currently being used from Australia to the Amazon. Supporting Indigenous-led tourism can be a fun, unique way to get to know a country and, more importantly, it can also help stop the speakers of local languages from becoming socially and economically isolated.

Related articles

Simple and flexible travel insurance

You can buy at home or while traveling, and claim online from anywhere in the world. With 150+ adventure activities covered and 24/7 emergency assistance.

Get a quote

No Comments