The Beauty of Slow Travel

From cabins in the woods to leisurely stays in the world’s great cities, ‘slow travel’ can be better for us and the planet.

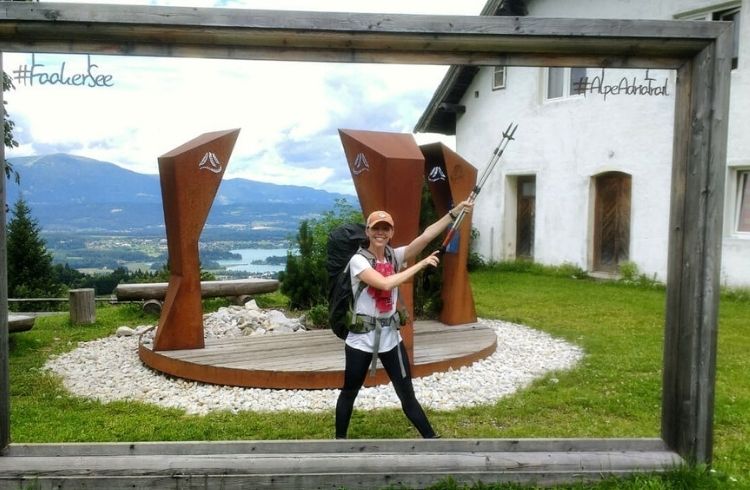

Photo © Joanna Tovia

Photo © Joanna Tovia

‘Slow’ in travel terms isn’t just referring to the speed with which you reach your destination. Sure, ‘slow traveling’ can mean trekking in the Himalayas or houseboating in Kerala, but it’s more of an attitude than a concept of time. It’s about taking a ‘slow’ perspective once you get there, spending more time seeing less.

- Happy days

- What is slow travel?

- The road more slowly traveled

- Why is slow travel responsible?

- The benefits of going slow

- What to do while you're there

Happy days

I once spent two weeks alone in a cabin in Norway. It was an ex-loggers’ hut on a hill surrounded by tall trees a long walk from anywhere. There was no electricity or running water, let alone Wi-Fi or phone reception. It was a genuinely Zen ‘chop wood-carry water’ experience.

I spent the long summer days – it didn’t get dark until 11pm – walking in the woods and swimming in the mirror-smooth lake nearby. There was unlimited, uninterrupted time to read, write and do nothing but listen and look at the birds and the trees. They were two of the happiest weeks of my life.

When I hiked out at the end of my slow and solitary fortnight, my first glimpse of civilization, a few suburban streets in a quiet town south of Oslo, made me feel like an alien. Everything seemed to be moving so, well, fast.

What is slow travel?

“Slow travel is the antithesis of overcrowded tourist hotspots, bucket lists and rushing around trying to see everything,” says travel writer Penny Watson, author of Slow Travel: Reconnecting with the World at Your Own Pace.

It also goes hand in hand with ethical, eco-friendly travel, she says. “Because it’s immersive, curious, authentic and interactive, slow travel makes us more mindful of our surroundings and when that happens, we can’t help but tread more lightly on the places we visit.”

And with periods of pandemic lockdown reminding us of the joys of living more simply, the idea of slow travel now seems to hold extra allure.

The road more slowly traveled

Once upon a time, everyone traveled slowly – by camel or on foot, by ship or in the saddle. Today there are as many ways to ‘travel slow’ as there are slow travelers to do them. Take a hike or a (local) train. Spend a week in a monastery. Do it at a ‘digital detox’ wellness retreat.

Why not rent an apartment in Toronto or Tangiers and test-drive local life for a while? You’ll get a fresh perspective on another culture, as it’s being lived right now, not frozen in time as it might be on an organized tour. The people living there might see you differently too.

When you’re not just another tourist passing through, you’re doing your bit for cross-cultural understanding. It’s a chance to be an ‘ambassador for peace’, according to the New York-based International Institute for Peace through Tourism, created in 1986 to make travel the world’s ‘first global peace industry’.

Why is slow travel responsible?

It makes intuitive sense. Slowing down, whether on safari in South Africa or hiking in New Zealand, gives us time to tune in to places, which helps us understand them – the way people live, the environmental and social challenges they face – and, ideally, adjust our actions accordingly.

Some of my most memorable travel moments have also been my slowest. Hiking in the mountains of Mongolia, a summer snowstorm forced my friends and me to shelter in a nomad family’s ger for the night, giving us an intimate glimpse of their daily lives; while living amid rice paddies in southern Kyushu on a working holiday opened my eyes to a very non-Tokyo Japan and taught me how to live communally and simply.

Even on short trips, slow travel is possible. Before COVID-19 turned it into a ghost town, I spent three days as an ‘untourist’ in Venice, taking slow walks, stopping to chat with artists and mask-makers, and taking pictures of cats sitting like ornaments in sunny windows.

At first, it felt like heresy to sidestep the must-see sights in one of the world’s great cities; then it felt liberating.

The benefits of going slow

Slow travel is good for us in other ways, too, calming our over-stimulated nervous systems, and giving us a break from the ongoing epidemic of busyness that infects our lives. It’s a chance to press ‘pause’ and, hopefully, ‘reset’.

“The essence of holidays, and therefore travel, is to get what you don’t get enough of the rest of the time,” writes Pico Iyer in his book The Art of Stillness.

“And for more and more of us, this isn’t movement, diversion or stimulation; we’ve got plenty of that in the palms of our hands. It’s the opposite: the chance to make contact with loved ones, to be in one place and to enjoy the intimacy and sometimes life-changing depth of talking to one person for five, or 15, hours.”

What to do while you’re there

One of the best things about staying in one place is that you can stop being just an observer and become part of the scenes unfolding around you. You can relax into being there, put your camera or phone away for a while, step into the pictures you’d otherwise be taking and experience them, body and soul.

Doing nothing is a core ‘slow travel’ non-activity, letting whims and chance encounters guide you. You could learn a new language: classes in the morning, real-life conversations in the afternoons. Take tango lessons in Buenos Aires, cooking classes in Tuscany, and art workshops in Arizona. Or just tune into the daily rhythm of life as it’s lived wherever you find yourself: by riding bikes along city streets, shopping with the locals at local markets, taking afternoon siestas.

Experienced the slow way, the world isn’t just your oyster; it’s also the pearl inside.

Related articles

Simple and flexible travel insurance

You can buy at home or while traveling, and claim online from anywhere in the world. With 150+ adventure activities covered and 24/7 emergency assistance.

Get a quote

No Comments